26.01.2023

For those who don't write code but work with Kubernetes

Kubernetes explained for non-developers

Kubernetes is currently the big thing in IT. But even developers struggle with it at times. And it’s infinitely more difficult for non-developers. But what can Kubernetes do exactly? What’s the difference between individual Kubernetes service providers? And what are the benefits of Kubernetes?

We’re going to look at these questions and provide a broad overview of Kubernetes and related subjects.

Content

What is Kubernetes?

Kubernetes is not a service offered by individual providers. Instead, Kubernetes is an open-source technology that enables the management and orchestration of applications packaged in containers.

In theory, Kubernetes can be downloaded for free on GitHub and then be made available on local servers or publicly (e.g. for a client).

In addition to this, there are also fee-based services that use Kubernetes as an open-source technology and provide further services on top of this that simplify Kubernetes and expand its potential. The most well-known examples for this are Azure Kubernetes Service (AKS), Google Kubernetes Engine (GKE) and Amazon Elastic Kubernetes Service (EKS). Most developers probably make use of such services.

With all these services, Kubernetes is still free to use – but the cloud resources or surfaces supplied by the providers are not. The management costs for EKS, AKS and GKE are usually pretty low. However, the computing and storage costs for resources charged by the services for cloud resources and surfaces can add up very quickly.

Back to the roots: monolith vs. microservices

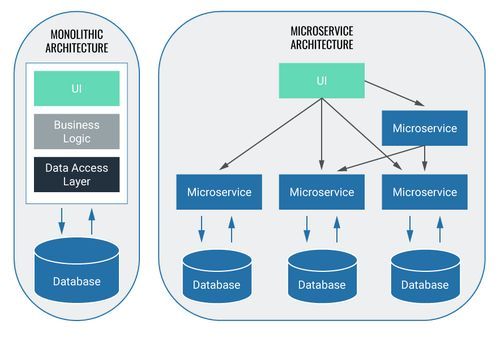

Put very simply, software development can be done via two different approaches: the monolithic approach and the building of microservices.

In the case of monoliths, all relevant components are included in one application. With microservices, on the other hand, there is an independent application for every component which only works on one specific part of the task. If one microservice requires the input of another microservice in order to get its job done, the respective microservices communicate with each other via interfaces. One advantage of microservices compared with a monolithic architecture: if one microservice malfunctions, it doesn’t necessarily make the entire system inoperable. However, neither of the two options is superior. At Blueshoe, we mostly use microservices for our work as they’re simply more beneficial for our purposes.

You don’t need to be using microservices to use Kubernetes. You can just as well employ Kubernetes to operate monoliths.

However, the software application will inevitably have to be packaged in a container if you want to use Kubernetes – and that’s possible with both monoliths and microservices.

Back to the roots: container

In order to grant non-developers a brief insight into why containers are used, let’s have a quick look into this – we’ll keep it simple!

Software containers can literally be regarded as just that – containers. They form a predefined environment within which the code can be run. A container therefore does not only contain the software – it also provides the opportunity to preconfigure the environment in which the software will be run (i.e. the container). Before the dawn of containerised software, the software always had to be run in various different environments, for example on different computers. So you didn’t just face the challenge of the software having to be free of errors, but every environment also had to be configured exactly the same way. With software containerisation, the container itself is the environment in which the software is run. So the software can be run on different servers without every single server having to be configured individually.

The most well-known provider that allows for the software packaging in containers is Docker. That’s why the term ‘Docker container’ is now commonly used – and in fact, it’s often used synonymously with ‘container’. In order to use Kubernetes, it’s necessary for the software to be packaged in containers. It doesn’t matter what technology is used to achieve this, though.

The size of the individual containerised applications is equally irrelevant (see above: monolithic architecture vs microservices) – Kubernetes can be used with both approaches.

The software that has been packaged in a container will be placed in a specified place. This is called a ‘Docker image’. When the software is run, this image is always referenced. This means that the software can be run in several instances if the same image is referenced.

OUR KUBERNETES PODCASTS

Tools for the Craft: Navigating the Kubernetes ecosystem

Michael and Robert are talking in depth about the ins and outs of local Kubernetes development and also provide some real coding examples.

More editions of our podcast can be found here:

Show moreWhat exactly Kubernetes does

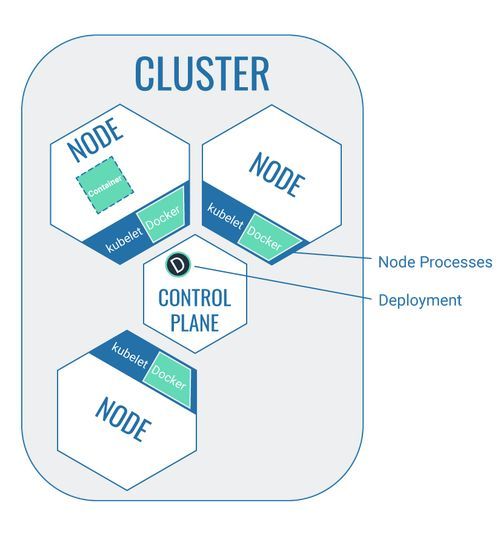

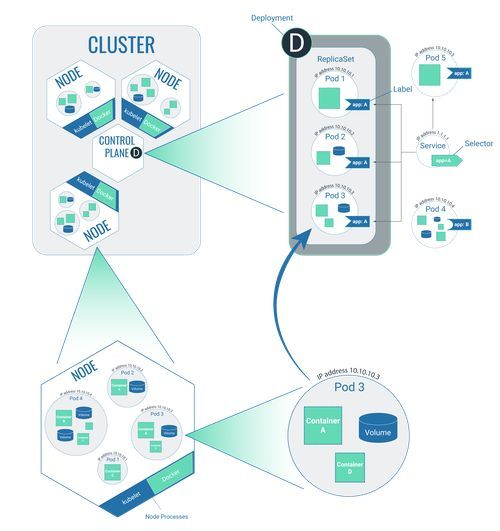

The open-source technology Kubernetes allows the management of containers within a defined environment. This environment needs to be clearly separated from its own surroundings. I.e., it needs to form a so-called cluster on a local system or be created in a public cloud, for example (client access can be restricted).

A cluster is a combination of different subcomponents which are required to run the Kubernetes technology – nodes and pods, for example. A node essentially acts as a server that runs the software application. In order for a software application to be run, the software needs to be packaged in a container and made available in the node (more about this later).

"Server vs. node" or: "pet vs. cattle"

Without Kubernetes, software is run directly on the server. In this case, the software is only available on this server. If the server can’t be reached, the software also cannot be run anymore.

Apart from the maintenance of the software itself, the maintenance of the server is also crucial with this solution. The server is like a pet: it needs looking after, requires attention and care, it’s meant to live as long as possible and hopefully, it doesn’t get ill. This is all to ensure that the server can deliver the software reliably.

In contrast, you could regard a node as an anonymous farm animal – much like cattle. Just a number, no name, no face. If a farm animal dies, it’s simply replaced by another one without much fuss. A large number of farm animals become a herd of anonymous individuals. Similarly, a group of nodes becomes a cluster.

If software is run on an individual server and the server cannot be reached anymore, the software effectively cannot be run either. The service can then no longer be used by the user. If the node, on which a containerised application is run, cannot be reached anymore, the container can be transferred to a different node in no time. This way, the software can continue to run.

This transfer of a container from one node to another is done automatically by Kubernetes. So going back to our example, Kubernetes is like the supervisor that makes sure there’s always one farm animal available to carry the application. Kubernetes is also often referred to as a service that orchestrates containers by assigning containers to available nodes – much like a conductor of an orchestra.

Kubernetes alternatives

Kubernetes isn’t the only service that orchestrates the software execution in a container on virtual machines (the nodes). Apart from Kubernetes, there are a whole lot of other providers: Docker Swarm, Nomad or Kontena, among others. You can find comparisons of these and other applications with Kubernetes in various online resources.

Why use Kubernetes?

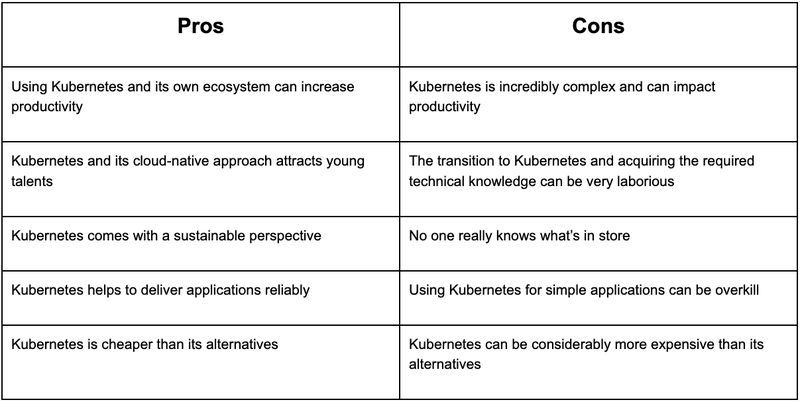

Kubernetes undeniably offers many benefits – but along with those come a few drawbacks, too. One ought to consider carefully whether or not to employ Kubernetes.

Here are some arguments for and against the use of Kubernetes:

With every benefit of Kubernetes, you’ll also find a drawback. So there’s no easy answer to the question ‘Should I use Kubernetes?’. Every reply is as unique as every software or every one of Blueshoe’s clients.

At Blueshoe, we have decided to make Kubernetes our go-to solution for orchestrating applications in containers. And that’s for a number of reasons:

- The projects we manage usually revolve around applications that are highly complex – the use of Kubernetes pays off in the case of such complexity.

- Our developers simply cannot be equally proficient in all alternative software used for the orchestration of containerised software. We therefore decided to become Kubernetes experts. Our knowledge can now be transferred to many other projects. The ramp-up phase was extensive, but we’re now benefiting from it.

- Kubernetes is supported by (almost) all cloud providers – unlike some alternative systems for the orchestration of containerised software. This means that there are no limitations when our clients choose their provider.

Should you host Kubernetes yourself or use a managed service?

As mentioned above, Kubernetes is an open-source technology. So its use is basically (licence-)free and can be hosted completely independently. AKS, GKE, EKS and other providers offer additional managed services that are designed to make the use of Kubernetes easier. And the use of these services is what such providers charge for.

So what do you do? Do you host yourself or pay money for a managed service?

When making your choice, two factors ought to be considered: For one thing, which ‘hardware’ and which services are supplied by the provider.

Secondly, one must not forget that there are staff costs to be paid if you host a Kubernetes cluster yourself – and these management costs aren’t exactly negligible. This article (date: 19/05/2022 – 18:05) clearly illustrates that if a cluster needs to be managed 24/7, at least 4 full-time developers have to be employed. This would ensure round-the-clock management, but would also cover staff shortages due to holidays and sick leave. When using a managed service, you still need a developer to oversee it – but in this case, it is assumed that one full-time position is sufficient.

What’s more, bear in mind that the individual providers’ cost structure for nodes, computing power etc. can sometimes be very unclear. What costs you can expect mostly depends on the scope of the information to be processed and the computing power required for this. The costs are often presented in a way that for people who aren’t familiar with the technical development and/or implementation of software (technical departments, for example), it’s hardly possible to estimate the necessary capacities and resulting costs. This means that the costs may vary significantly depending on the changing user traffic, for example, as this would require considerably more computing capacity. You should therefore always do a rough cost estimate for a managed service and allow for some buffer space in your budget. You should also always include a developer who knows the subject matter when making these calculations.

What do you need to build Kubernetes?

Let’s have a closer look at Kubernetes itself in this second part. We’ll explain the terminology and clarify how exactly they relate to one another.

Developer or no developer: If you’re checking out Kubernetes for the first time, you can find a great initial overview of the specifics here (date: 07/07/2022 – 8.30). In the following, we will mostly refer to this source.

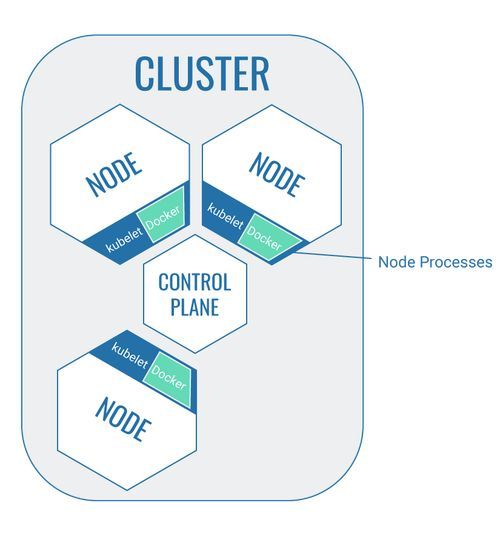

Cluster

Kubernetes can only be used within a specified environment. The cluster itself cannot be equated with Kubernetes. But as a technology, Kubernetes offers the possibility to create a cluster that sections off various elements from its environment.

So in the context of Kubernetes, a cluster is a combination of different components required for the use of Kubernetes which has to be clearly separated from its environment. New components (like new nodes, for example) have to be explicitly allocated to the cluster by a developer and cannot get to the cluster automatically.

Node

A node is a virtual machine or a physical computer. It’s a part of the cluster which runs the software that is packaged in containers. The containerised software itself is placed on the node via pods.

The node itself consists of smaller applications in order to carry out this work:

- Kubelet: Every node contains a so-called Kubelet which manages the node autonomously and communicates with the control plane via API.

- Tools to operate the containers within the node: The node provides space for the containerised software. It may, however, become necessary for work to be carried out on the containerised software. To allow for work to be carried out on the software (starting it, for example), the node has tools that can access the software located in the container within the node. It’s a special tool that manages Docker containers.

Additionally, nodes can also contain pods, which in turn contain containerised software. But more about that later.

Control Plane

The control plane is the core of Kubernetes – the executive Kubernetes instance (like a control centre) that coordinates all activity within the cluster. A control plane is also a node, but with the specific task to coordinate the cluster.

The control plane provides an API to communicate with the other cluster components.

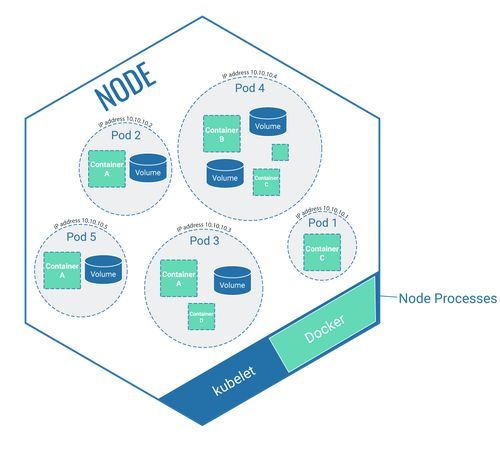

Pods

The term ‘pod’ is probably one of the most used words in the Kubernetes vocabulary. Sadly, though, they have nothing to do with Star Wars – they are in fact the smallest units in the Kubernetes universe.

As the smallest autonomous units in the cluster, pods effectively combine several elements that are placed in the cluster during the deployment process. Essentially, they’re like pea pods, and they can enclose elements like the following:

- Separated storage units, for ex. volumes

- Cluster-specific IP addresses

- Information about how containers are operated, for ex. image versions of the application, information about ports etc.

Every pod has its own IP address which is only known within the cluster. This means that the individual pods can only be accessed within the cluster and cannot be controlled from the outside.

A node can contain a number of pods. Every pod is only ever allocated to one node and always remains on this node until the node is deleted or ‘dies’ due to errors. If this happens, the pod ‘dies’, too. In this case, however, the pod can be recreated on a different node via the deployment process (see below) and therefore enjoys ‘eternal life’.

ReplicaSets and the deployment process

We’ve now covered the individual components of the cluster: the node, the control plane and pods. But how do these components interact with one another, and how do they help contribute to running the developers’ code correctly?

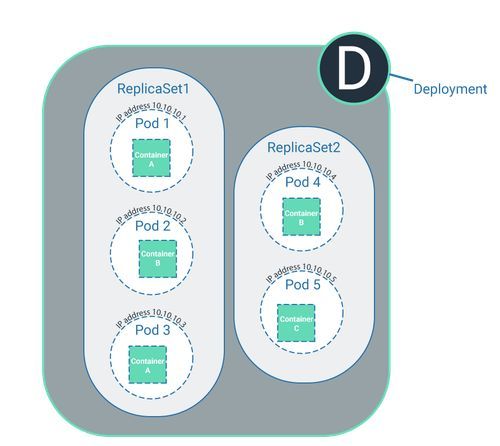

That’s where the deployment process comes in. This is the stage when the developers place the code in the cluster. During the deployment process, the developer specifies how often individual software components should be run.

It is also decided which software should be run in general. The software is packaged in a container image and the image is placed in a specific location (see above). If it is decided during deployment that the software should only run once, the number of ReplicaSets equals 1 which means one pod is established for this task. If the software should be run multiple times, the number of ReplicaSets might equal 3, for example. Three pods will now be established in the ReplicaSet which all reference the same container image.

If the ReplicaSet equals 3 and is therefore linked to three pods, these three pods can be run on the same node. While all three pods run the same software via the reference to the container image with the same code, they are indeed different pods. It is therefore still correct that every pod only exists once in the cluster and is only ever assigned to one node.

A deployment can cover multiple ReplicaSets which either refer to different or to one and the same software.

As mentioned previously, the deployment process offers the benefit that, should a node be deleted or malfunction, for example, the pod along with its contained software can be recreated on a different node. The information of how a pod is to be run within a cluster is described during deployment. The step of assigning the pod to a node is carried out by a service (see below).

With Kubernetes, in order to start and manage the deployment, the command-line interface is used – the Kubectl. Kubectl is less relevant for non-developers, but it’s still worth mentioning this term at least once at this point.

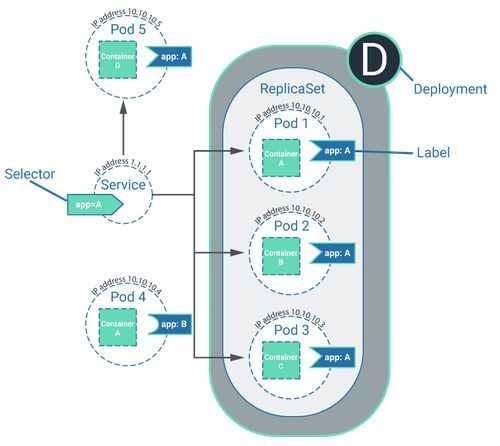

Service, label and selector

A service in Kubernetes has nothing to do with a ‘managed Kubernetes service’ (see above), but is in fact a part of the cluster. A service could be considered as an abstraction which gathers pods together in a logical sense and defines how the pods can interact with one another. They do not interact with each other directly, though. Instead, the pods can be assigned labels. This service also includes a complementary selector. Pods can then interact with one another via the labels on the pod and the selectors of the service.

The Cluster: a summary

In a nutshell, a cluster consists of several nodes, with one of these nodes acting as the control plane.

The software that is to be run in the cluster is packaged in a container and has been placed in a specific location whilst acting as a container image. So the software isn’t actually placed in the cluster itself, but the cluster only ever references the container image.

During the deployment process, it is defined which software is to be run in what sort of manner (how often, for example). To do this, one or several ReplicaSets are created. The deployment process is carried out on the control plane.

After the deployment, the pods that were defined during the deployment process are created in the cluster and distributed to the different nodes.

Services in the cluster have selectors, and pods can access these selectors via complementary labels. It’s possible for the pods to interact with each other via this lock-and-key principle. A pod can only interact with another pod if it has a label – if it doesn’t have one, it acts on its own.

Cluster size

The advantage of Kubernetes is that the system can recognise when a node (= virtual machine) isn’t operational anymore. If the software was running on one individual server, you wouldn’t be able to execute it anymore at this stage. Kubernetes, however, can automatically assign the software within the container to another, functional node. For this reason, a cluster in the production system should contain at least 3 nodes. One of these would be the necessary control plane, while the other two nodes would contain the software to be run in pods. A pod would only run on one node – the remaining node would ‘only’ be on standby in case the other malfunctioned.

Conclusion

Kubernetes is an open-source software that can be used by anyone, free of charge. It’s a service that runs software and offers a lot of benefits compared with the operation of autonomous servers.

What’s more, providers like AKS, GKE or EKS offer further services associated with Kubernetes which are designed to make the administration easier. These services come at a price, though, and it’s not always that easy to keep track of the various charges.

Kubernetes is a technology that consists of a set of individual components. A cluster is required for its operation – and this can only be created once nodes, pods and the control plane interact with one another.

Kubernetes is not a miracle cure that is equally suited to every kind of software. Whether Kubernetes is suitable for the operation of a specific software or for the entire organisation needs to be assessed on a case-by-case basis. This also applies to the decision of whether or not the services by providers like AKS, GKE or EKS should be purchased.

We hope we were able to give you a good overview of what Kubernetes is, explain how it differs from other technologies for running software and – tragically – to confirm that a Kubernetes pod has nothing to do with podracing from the Star Wars films.