30.08.2021

How to master the challenge

Migration to cloud-native

The ‘cloud-native’ development process is an integral part of our projects. However, it can be quite a challenge to migrate existing projects into the cloud-native workflow. In this blog post, we’ll use three examples to show you the steps that a migration to cloud-native requires.

In this blog post we will cover

The first obstacles have been dealt with. We know why we want to use cloud-native development, our developers have been trained to utilise the process and new projects use cloud-native right from the start. However, migrating to cloud-native can still be a challenge. That's why towards the end of this article, you’ll find out in what way Unikube can assist the migration.

Type of migration

With the migration, we ultimately want our production and staging/testing systems to be hosted via Kubernetes (K8s) and also for our developers to develop with private or individual Kubernetes clusters. If you want to check out what the local development with Kubernetes looks like, check out the blog post "How does local Kubernetes development work?".

Depending on the development process, an existing project includes different elements on which you can build during the migration, or which have to be prepared first. One of the main aspects is whether the project already uses container images or not. We will have a look at three example projects which differ from one another with regard to development procedure and hosting:

For one, we have a project which has been developed locally using Vagrant and which is hosted by a tech stack of uwsgi and nginx (a pretty common stack for Django projects). The other two projects already utilise Docker images. For the local development, both projects use Docker Compose while one project is hosted with Docker Compose and the other with Kubernetes.

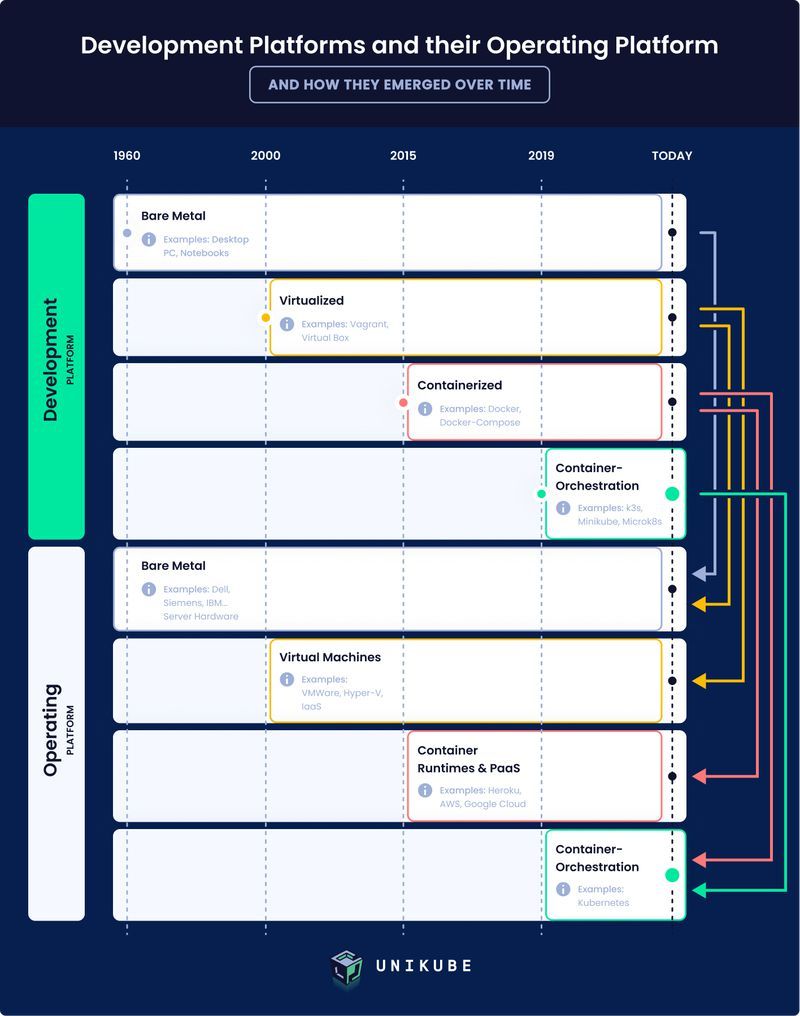

In the following graphic, which illustrates the temporal development of development and hosting systems, we can clearly assign our example projects. For this blog post, we’ll ignore the first stage, 'Bare Metal'. In the development platform section, our three projects can be found under the stages ‘Virtualized’ and ‘Containerized’. In the operating platform section we can follow the arrows and find our projects under 'Virtual Machines', 'Container Runtimes & PaaS' as well as 'Container-Orchestration'. The goal is for all three projects to appear both in development and operating under the stage ‘Container-Orchestrated’.

Example 1: Local development using Vagrant

Vagrant was developed to display the development environment in a completely virtual machine (VM) in order to simulate the production environment here in the best possible way. As no complete VMs are used in the cloud-native process anymore and as instead, the application along with its environment variables is put into the container, the first step is a migration to Docker.

To do this, a Dockerfile has to be created for the scope of the application. At this point, it might also make sense to consider which parts of the application could be subdivided into individual services. Previously, there was only one Vagrant VM and in the worst-case scenario, the application would become one massive monolith. At the very least, systems like a databank or a cache should not end up in the Dockerfile but should instead be configured as individual services.

The second step is to create the Kubernetes manifests – via Helm charts, for example. This means that for all required services, Helm charts have to be created which then generate the respective K8s resources.

Finally, you ‘only’ have to transition the development process to Kubernetes. This means that our developers have private or individual clusters are their disposal. On the one hand, this could be local clusters which are simulated via k3d, microk8s or minikube. Or one the other, these individual ‘developer clusters’ might also exist remotely – meaning it’s a real K8s cluster, but it’s only used by one developer.

Example 2: Local development and hosting with Docker Compose

Our second project employs Docker Compose in the development as well as in the hosting of the production system. This means that we have one or several Dockerfiles and that right at the start of the project, we have already thought thoroughly about the different services the application will need. These are displayed in the Docker-Compose.yaml.

The main part of the migration consists of the creation of the Kubernetes manifests. Just like with the previous project, this can be done by using Helm charts. When using Helm charts, the Kubernetes manifests are easier to maintain. This particularly makes a difference in larger projects. If the deployments are built quite similarly, for instance, this can be displayed more effectively in Helm templates (keyword: DRY). Should this not be a requirement, you could also create the manifest files directly from the Docker-Compose.yaml. To do this, Kubernetes provides the command kompose. Using it is easy – a simple kompose convert will suffice to create the files.

Naturally, in this case the local development process will then have to be transitioned to Kubernetes, too.

Example 3: Local development via Docker Compose, hosting via Kubernetes

With this project, we have already subdivided our services and we also have one or several Dockerfiles. For the local development, Docker Compose is used while the hosting takes place via Kubernetes. Thus, the only migration step is the transition of the local development process to Kubernetes. Other than that, the production environment for the local development always has to be simulated in the Docker-Compose.yaml. This does require a certain amount of extra effort on the one hand and on the other, it does create the problem that the local environment doesn’t quite match the production environment. This means that unexpected problems or side effects can occur during deployment.

Challenges during migration

For the migration to cloud-native in our example projects, a few challenges need to be overcome. For one, these challenges apply to the actual migration itself. But then they also apply to how the developers receive the transition to the local development processes and to any additional tools that the developers might have to master first. We’re also assuming that an operations specialist with extensive Kubernetes knowledge is part of the team who can develop the Helm charts.

This brings us to the next question: Which obstacles remain, from a developer’s point of view, when migrating all projects to cloud-native?

- Learning how to use kubectl in order to enable the direct interaction with the cluster.

- Live code-reloading: When the code is changed, it should be possible to test the alterations as quickly as possible – without having to first build a new Docker image and deploy it in the local cluster. This is possible via Gefyra.

- For most developers, the debugger is undoubtedly an important part of an optimal development process. With a local Kubernetes cluster, this debugger has to be explicitly configured again. In a Python environment, for example, you do this using python remote debug.

So our developers have to learn at least the basics of three further tools in order to utilise the whole scope of features which the Docker Compose setup has made available. This isn’t an impossible task, of course, but it does require additional effort.

How does Unikube support the migration?

Finally, we’ll have a quick look at how Unikube can come into play when migrating to cloud-native. Unikube essentially works like a kind of ‘wrapper’ for various tools or features. This means that a developer working with Unikube will only have to learn one tool, rather than several different ones. The developer will thereby also not have to acquire any detailed Kubernetes knowledge anymore and will also not have to directly interact with the Kubernetes cluster.

One of the key aspects when developing Unikube was for it to be as easy and comfortable to use via command-line interface as possible. The goal here was to get to a certain convenience level that we’re used to from Docker Compose. And through this, it also just so happens that we eliminate all that Kubernetes complexity!

Stay tuned for upcoming Unikube features and feel free to send us any feedback you might have – via GitHub, for example.

An alternative to telepresence

We decided to create an alternative to Telepresence 2. Check it out if you like: https://gefyra.dev

Also, have a look at my talk at Conf42 about debugging a container with sidecar using Gefyra.

Gefyra